Lessons from Draft Cycles Past, Present and Future

Note: this article was originally published at The Stepien on July 8, 2022

With my first full NBA draft cycle complete as a consistently active analyst, I figured it would be useful to take a step back for a “forest through the trees” piece. Noting the differences between your own appraisal of prospects compared to the NBA can feel like chasing one’s tail, but useful all the same in nailing down what you do and don’t cherish in teambuilding.

My archetype project was fun, slicing into four different buckets the ways players can contribute to winning at the highest levels (my final board with links to all four Stepien pieces can be found here), but is just one of endless approaches available for analyzing prospects.

In the first third of this piece I’ll look at the most significant differences between my own rankings and where players were taken (or not) in the actual 2022 draft. In the second third I’ll use my archetype studies to see if my analysis of the 2021 draft would change from then to now. Both seek to understand what my process valued most dearly, perhaps unveiling some of the flaws in the archetype-centric approach in addition to some strengths, all in favor of getting better next time around.

The final segment will refine my approach, reaping these lessons to the future, in anticipation of the 2022-23 draft cycle. One of my favorite items about draft work is you get a chance to fully reset your philosophy each cycle if you so choose, and I think it’s immensely helpful to take a step back for annual self-evaluation.

2022 Draft Recap: My Biggest Differences

To try to be at least somewhat objective with the differences between my own board and the 58 picks of the 2022 draft, I utilized Kevin Pelton’s draft pick trade value chart to benchmark where I had my ranks compared to the league. I then cross-referenced the difference broken out by my archetype system to see which types I over- or under-valued. The results:

Difference #1: Identifying Tough Shotmakers

My single biggest difference to the draft was how I prioritized Jaden Hardy (and, to a much less extend, Julian Champagnie) compared to Bennedict Mathurin and Ochai Agbaji. Hardy went over a full round later than Mathurin and half round later than Agbaji, an inexcusable difference according to my personal board.

On the surface this difference makes sense, as the best skill for all of Hardy, Mathurin and Agbaji is shooting, where Jaden shot 32% from three compared to 37% for Bennedict and 40% for Ochai. But the surrounding circumstances all make me much more confident in Hardy’s trajectory.

First, the difference in percentages isn’t as significant as those percentages suggest. Hardy shot 36% (25-69) on deep twos compared to 29% (25-85) for Mathurin and 27% (31-116) for Agbaji. This wasn’t an aberration for Mathurin and Agbaji either: they shot a similarly disappointing 27% and 26% on deep twos last year. Hardy’s 81% shooting from the line also compares favorably to Mathurin’s 76% and Agbaji’s 74%.

Beyond that, Hardy’s deep threes and deep twos were both, well, deeper. The former #2 HS recruit by ESPN took the most deep threes (159) of any of the Ignite youngsters with 87% of his threes coming from 25+ feet. His comfort against the elevated level of competition increased as the year went along, as can be seen in his rising three-point percentage from month-to-month.

Specifically, Hardy’s off-ball game advanced significantly in the second half, disproving the narrative of him needing the ball in his hands to be effective. Over the first half of the season, he shot a subpar 0.9ppp on 1.8 catch and shoot attempts per game before rising to a very good 1.2ppp on 2.9 attempts per game in the second half.

Let’s take a deeper dive into what happened. In watching all his attempts in sequence, it seems Hardy was a bit overwhelmed at first by the competition. With his reputation as an elite shooter, teams hounded him on the perimeter to start the season, forcing him to rush shots which either clanked off the side of the rim or at times were even blocked.

His form was all over the place, particularly with regards to set point and posture:

In these three stills we see him at “spring point,” locked and loaded, starting to push up through his base. But his posture, footwork and ball position as he is about to rise are all vastly different. Facing NBA-level defenders for the first time can throw off even good shooters’ mechanics, and Hardy’s fell apart quicky. To compensate for feeling rushed, Hardy’s wrist flexion and lean-back, already severe, became even more exaggerated, taking the energy out of his lower body with an awkward release path through the roof.

Then, by Hardy’s fifth game, the team added Scoot Henderson to add some playmaking just as teams decided to not guard Hardy as tightly. This gave him just the space he needed to get his form in order, as through the rest of the season his mechanics tightened up significantly, gaining consistency game by game:

To display the practical result of these mechanical changes, I’ve compiled all of his good set + good flow catch and release shots over the course of the season, with corresponding game in top-left corner text. As you can see the good became more and more common as the season went on, culminating in some massive performances with five consecutive 20+ point performances to close the season. He became more confident not just spotting up, but spotting up off movement and with increasing close-out pressure as defenders respected his shot once again. By the end of the season his old confidence has returned, and this form appears locked into muscle memory.

Returning to the question at hand, especially when taking into consideration Hardy’s improvements over the course of a professional season, I do not see anything that explains the gap in draft position. While Hardy is not the same level of explosive vertical athlete or as physical as Mathurin or Agbaji, he does have more guard skills, showing progress as a driver and PNR operator as the season went on as well. He may not have the same help side rim protector ability upside as Mathurin or especially Agbaji, about an inch shorter than those two, but, despite his reputation, he plays hard on defense and has decent instincts.

In my opinion, the Mavericks may have snagged the steal of the draft with a now-underrated game-ready guard. While he may not be the high usage iso fiend some hoped he would be as a high school recruit, this versatile on-and-off ball route seems better, as does playing off of a primary like Luka.

Difference #2: Hybrid/Wing Rim Protectors vs. Drop-Only Bigs

Here I have more of a difference in teambuilding approach. I ranked a bevvy of help-side (Josh Minott, John Butler, Kendall Brown, Dyson Daniels, EJ Liddell, MarJon Beauchamp, Jabari Walker) and versatile (Duren, Koloko, Kamagate, Barlow) rim protectors higher than they were taken, if they were drafted at all. In comparison, drop-only bigs Mark Williams and Walker Kessler went much higher than I would have taken them.

I prefer a team-centric, flexible rim protection approach to a single-burden one, as more options for shotblocking and ways to constrict a defense are always preferable to locking into a single approach. The help-side rim protectors mentioned above should all be able to guard on the perimeter while also monitoring what’s happening near the rim, at least in an actualized version of their talents (all draft picks are swings, after all). To be able to flex small-ball versus dual-bigs makes a team much tougher to scheme for in the playoffs, and also gives much more flexibility of personnel to place more offensive-minded players around them.

While a true elite drop big can still help you immensely in the regular season and in the right playoff team construction, it is very difficult to find that kind of difference-maker and I believe both Williams and Kessler fall short. I hinted at this in their omission from the top ranks of my rim protector piece, as I failed to see the type of qualities needed to reach that kind of level needed to anchor a high-level defense.

Mark Williams is indeed enormous in standing reach, clocking in at a shocking 9’9’’, which goes a long way for filling this role, and Kessler is still an impressive 9’5’’. But I think Williams and Kessler are more uniquely big than they are unique for bigs. Williams struggles with the stronger centers, as his functional lower body strength is quite poor which mixes poorly with his high center of balance. A major benefit to the drop scheme is being able to clear out the paint for defensive rebounds by keeping an enormous human in the paint, but if Williams can still be shoved around that is a major issue. Kessler, for his part, didn’t show the discipline of footwork that elite drop rim protector prospects display, (perhaps contrary to popular belief) typically present even at a young age. He had a historic number of blocks, but being overly jumpy at the college level isn’t nearly as damaging as in the pros.

The margins for being an elite drop big, the type who would be a positive contributor in the playoffs, is quite narrow, and these two are not the ones I’d bet on to do it. Drop bigs can only cover up so much for perimeter failings, and I’d rather man the wings with those who can compensate.

Difference #3: Flawed Creator Bets

With fewer elite creator prospects at the top than usual, evaluating 2022’s initiators took more creativity than usual. For my part, at least as an armchair GM evaluating talents from my laptop, I would be much more comfortable taking big swings on players with single glaring flaws in the presence of rare, positive attributes elsewhere. Here I’m talking about Jaden Hardy (don’t need to go into him any further), but also Tari Eason, Malaki Branham and Alondes Williams.

Eason and Branham are below average for where you’d like initiators to be as distributors, both seemingly limited in consistency of vision despite showing passing flashes. But with outlier skills in Eason’s bruising quick feet on drives for a power wing (6’7’’, 7’2’’ wingspan with the biggest mitts in the class) and Branham’s pull-up craft and elite touch, they both have a route for reps soon into their careers. Those reps are gold for developing initiators, and the easiest way to branch out from simple to complex passing reads is just that. Having a “fastball” is crucial to buy you the time to develop counters.

Alondes is a unique case, a hyper-creative passer who knows where his four teammates and their defenders are at all times. That ability simply very rarely comes along, especially in an ultra-physical, elite finishing (66% at the rim with 74% of makes unassisted) 6’4’’, 6’7’’ wingspan, 205-pound frame. Alondes was one of the ten fastest measured sprinters in the combine, barely slower than Terquavion Smith, a remarkable feat for his bulky frame. That combination of athlete and passing vision is rare, as is Williams’ ability to time skips or hit-aheads when the defense least expects it. The edges all need smoothing, particularly his handle and decision-making, but both are improving and unlocking new passing ideas along with it. That’s worth a late first/early second round bet, to me, yet he was not drafted at all.

2021 Draft Review:

In addition to inspecting, essentially, in how much agreement the league was with my archetype analyses this draft, I thought it would be worthwhile to see where this approach would have fallen short in evaluating the prior draft’s top prospects.

In no means do I think my approach was all-inclusive, rather a first step towards covering draft analysis to be built upon. This may help guide us for the cycle ahead.

Takeaway #1: The 2021 Class Was Really, Really Good

This should come as no surprise, but it truly is shocking to go through this class in comparison to 2022’s. First, the depth of creator prospects is an ocean compared to 2022’s trickle. Initiators are unsurprisingly the most coveted types of prospects, the exact type of gamble most teams in the lottery want to make. This year non-creator prospects went as high as #9 (Sochan), #14 (Agbaji) and #15 (Mark Williams); in comparison for 2022 only Josh Primo in the top 15 would qualify (and even now it seems he may have a chance with much more creation upside than shown in college), with many very good initiator options in Tre Mann, Josh Christopher, Bones Hyland, Cam Thomas and Jaden Springer all going in the 18-28 range and Jared Butler, Sharife Cooper and BJ Boston in the second round. One for the ages.

Takeaway #2: The Archetypes Work How They’re Supposed To

In 2022 there wasn’t a single prospect who featured in all four of my archetype pieces, but for 2021 we see both Jalen Suggs and Scottie Barnes as “four quadrant” prospects. They can run some offense, defend at the rim, connect their teammates with strong defense and passing, and can make some scoring plays (in college Scottie was incredible at beating trapping PNRs, Suggs at shooting off the dribble).

Deeper into the draft, I was very low on Alperen Sengun as a creator or defensive prospect but his use of body and passing ability clearly show him as one of the top Body Bagger Connectors in the class. Chris Duarte as well looks like an obvious top 20 prospect in retrospect, as his hybrid of elite wing connector and tough shotmaker is a rare combo. On the flip side, my love for Cam Thomas’ game is diminished somewhat by his single-lane developmental trajectory. I still believe in him as a scorer, but if that doesn’t work out as planned he has little other route to rely upon.

By marking out these lanes of development it’s easier to see the rare and multifaceted prospects versus those potentially siloed into a difficult development path. Archetypes aren’t meant to define a prospect’s ability, as flexibility is always useful in draft analysis, as also seen by…

Takeaway #3: Relying Only on Past-Year Performance is a Major Flaw

For the sake of time in summarizing my views on hundreds of prospects, it was often much easier to simply benchmark against current year performance. While more often than not this will be the more accurate representation of a prospect’s abilities than their prior seasons, it can miss some key details.

Stats queries have been quite popular in the scouting world, as barttorvik.com’s NCAA stats database is incredibly useful for summarizing a player’s contributions. But these underestimate player context as well as year-to-year randomness. For one of the stranger examples, if you were searching for a minimum athleticism level by searching for prospects with 1+ or 5+ dunks in a season, you would capture Desmond Bane’s freshman (6 dunks), sophomore (7) and junior (11) seasons, but not his senior (0). Clearly Bane did not become a worse athlete all of a sudden, and no lack of athleticism has hampered his on-court contributions.

But the most important aspect is how prospects are often marginalized by role, the most glaring examples being Franz Wagner and Scottie Barnes. Based on their 2020-21 NCAA performances, I likely would have marked Wagner as only a “silver” level creator prospect, and Barnes a “bronze.” But both in their rookie seasons clearly showed they could be more than that with looser reins than they had in college, and I believe these single-season archetype studies would have underestimated them on their college tape alone.

Looking at his pre-college tape, we see a Wagner more consistently aggressive attacking the rim, in fact astonishingly so for a skinny kid playing in a pro league. His long strides and functional handle for length are easily apparent, as he glides past opponents and is effective on long-gather layups. There was a narrative about Wagner being afraid of the spotlight and shy shooting the ball at Michigan, both laughable when spending any amount of time watching his earlier tape. In fact, he went 6-6 in the second match of the German league finals, including a huge three with 15 seconds left to bring Berlin within a point of Munich. All at age 17.

Barnes’ upside as a creator, meanwhile, was much tougher to discern even when searching for it. The commonality between him and Wagner are the long strides and handle for length, both confident in their movements if not always polished in final execution. Barnes, however, looked like a total non-shooter, often not being guarded even in the midrange. But he did show endless sparks of creativity to compensate, and the same infectious energy that has made him an immediate favorite of both fans and his teammates.

The lessons all point to being creative in your evaluations, and if there is any earlier tape you think might inform the more complicated prospects, (NOTE TO SELF) watch it.

Lessons for the 2022-23 Cycle:

I hope to take all of these lessons to build a better process for the coming year. Now that I have archetypes set and a mental model for how to identify players who fit the molds, I plan on pivoting to a one-by-one evaluation technique.

By focusing exclusively on one prospect at a time, I can build a better narrative not just for how they are what they are but with more insight into what they could be.

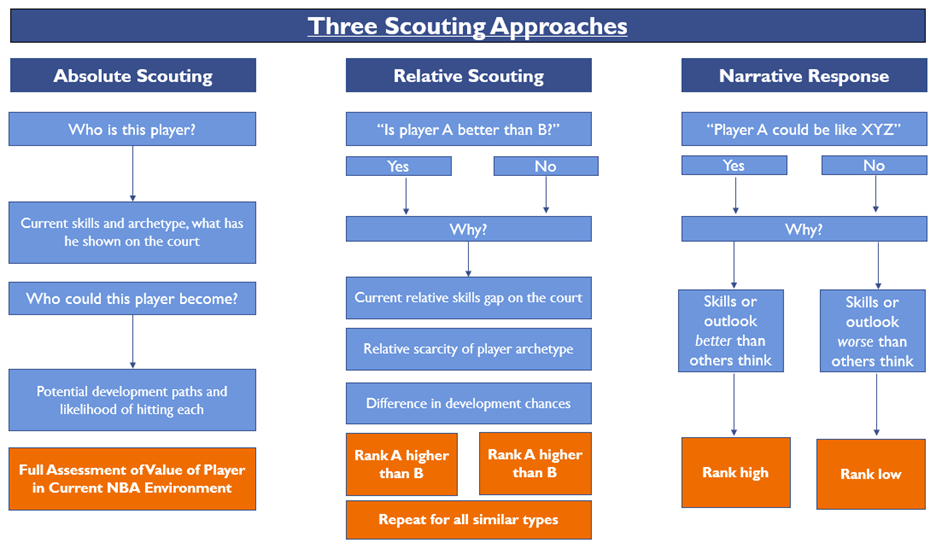

Second, this method also allows for an “absolute scouting” lens instead of the relative scouting model I was applying this past cycle. Each prospect should be viewed among their peers in the draft, of course, but to build a full image of their level as a prospect must be viewed individually. This approach also reduces the “narrative response” bias that I’ve noticed in my own scouting.

Here’s an illustration of the two types of scouting I’ve been guilty of, and, in the far left column, what I aspire to fulfill for next cycle:

Essentially, narrative response scouting means benchmarking your view to the public perception of a prospect to then move a player up or down your board based on your perspective in comparison to this common narrative. An example of a mistake I’ve made with this would be Patrick Williams in 2020, where I thought his scoring ability and immediate defensive impact (particularly lateral movement) were much worse than were being discussed as he went #4 overall. In that case, I plummeted him way down my board last second to the late first, a drastic overcorrection simply due to my own narrative fighting rather than looking at the facts of his game more objectively.

To compensate for this, I switched to relative scouting this past year, stacking up each player next to their peers for similar types. If I know one player is a better connector bet than another, it is easy to put that player higher, relatively. But this often misses the forest through the trees, especially for players more elusive to a specific archetype. It will remain to be seen where my 2022 board will have these failings, but I’m curious to find out.

Regardless, going forward I want to give each player his fair due in his own spotlight before comparing across his peers. Beyond giving a fuller representation of a prospect as a basketball player, it also does as a person, giving a better understanding of their successes or failures within their own personal trajectory. This holistic approach is truly the only way to project a player into the future. This is why I felt I had a very good grasp on Dyson Daniels, the only player I profiled in-depth, as his personal, drastic transformation over the past few years gave me more comfort to place him in the early lottery.

With all that said, I look forward to refreshing for the new cycle, as you can expect the first profile to arrive in the coming weeks.